- Home

- Gerald Vizenor

Native Tributes

Native Tributes Read online

NATIVE

TRIBUTES

GERALD

VIZENOR

NATIVE

TRIBUTES

‹|› HISTORICAL NOVEL ‹|›

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown, Connecticut

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2018 © Gerald Vizenor

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed and typeset in Fairfield LH by Kate Tarbell

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

NAMES: Vizenor, Gerald Robert, 1934– author.

TITLE: Native tributes: historical novel / Gerald Vizenor.

DESCRIPTION: Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2018.

IDENTIFIERS: LCCN 2018008567 (print) | LCCN 2018014228 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819578266 (ebook) | ISBN 9780819578259 (pbk.)

SUBJECTS: LCSH: Indians of North America — Political activity — Fiction. | Veterans — Political activity — United States — Fiction. | GSAFD: Historical fiction

CLASSIFICATION: LCC PS3572.I9 (ebook) | LCC PS3572.I9 N38 2018 (print) | DDC 813/.54 — dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008567

5 4 3 2 1

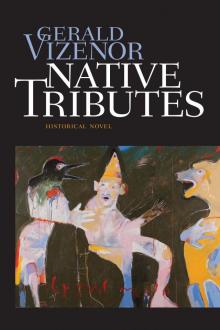

Painting by Rick Bartow, Crow Magic. Courtesy of the Froelick Gallery.

IN MEMORY OF NATIVE VETERANS

of the Bonus Army

‹|›

CONTENTS

1 › Dummy Trout 1

2 › Diva Mongrels 10

3 › Tombstone Bonus 20

4 › Double Prohibition 28

5 › Bagman Civics 33

6 › Anacostia Flats 40

7 › Enemy Way 47

8 › Cortege of Honor 56

9 › Look Homeward 63

10 › Liberty Trace 75

11 › Night of Tributes 92

12 › Ritzy Motion 97

‹| 1 |›

DUMMY TROUT

Dummy Trout surprised me that spring afternoon at the Blue Ravens Exhibition. She raised two brazen hand puppets, the seductive Ice Woman on one hand, and the wily Niinag Trickster on the other, and with jerky gestures the rough and ready puppets roused the native stories of winter enticements and erotic teases.

The puppets distracted the spectators at the exhibition of abstract watercolors and sidetracked the portrayals of native veterans and blue ravens mounted at the Ogema Train Station on the White Earth Reservation. The station agent provided the platform for the exhibition, and winced at the mere sight of the hand puppets. He shunned the crude wooden creatures and praised the scenes of fractured soldiers and blue ravens, an original native style of totemic fauvism by Aloysius Hudon Beaulieu.

The puppets were a trace of trickster stories.

Dummy was clever and braved desire and mockery as a mute for more than thirty years with the ironic motion of hand puppets. Miraculously she survived a firestorm on her eighteenth birthday, walked in uneven circles for three days, mimed the moods of heartache, and never voiced another name, word, or song. She grieved, teased, and snickered forever in silence. Nookaa, her only lover, and hundreds of other natives were burned to white ashes and forgotten in the history of the Great Hinckley Fire of 1894.

Dummy stowed a fistful of ash in a Mason jar.

Snatch, Papa Pius, Makwa and two other lively and loyal mongrels lived with the mute native puppeteer in the Manidoo Mansion, a shack covered with tarpaper near the elbow of Spirit Lake on the White Earth Reservation.

The lakeside house and place name were overstated in mockery, and yet that shack with a slant roof and two small windows became a monument of native memories, of the endurance of a gutsy native voyageur who tutored soprano mongrels and revived the magic of native puppets. The mongrels were natural healers and devoted to the motion of hand puppets, caught the sleight of hand, the tease, crux and waves of gestures, and retrieved the murmurs, wishes and whimsy of the silent stories and mercy of memory.

Dummy Trout mimed, cued, teased, and signaled at ceremonies, parties, parades, and reservation events, and forever doted on that eternal native spirit in the bounce, jiggle, and conscious sway of the hand puppets.

Dummy was a silent storier of truth.

Snatch, a blotched blond spaniel and retriever, was the only migrant mongrel from outside the woodsy reservation, and the nickname described a moody manner at meals, as he snatched food and ran away to eat. Snatch and hundreds of other mongrels were abandoned with horses, pets, and even houses, barns, chapels of ease, and costly machinery during the Great Depression. The land was timeworn, farm families were evicted, even grease monkeys were suspended, and for thousands of veterans railroad boxcars became homes.

The mongrels avoided the vagrants and roamed in packs to survive, but most of the twitchy mongrels, once favored as escorts in the outback, slowly died of hunger, or were tracked down as puny prey by other animals. Snatch was enticed by the voice of a coloratura soprano, as stories of his rescue were told many times, and wandered with caution to the recorded sound of opera music at the Manidoo Mansion.

Papa Pius was nicknamed in honor of the succession of popes, an ironic gesture of pagan mongrels and spirited hand puppets. Makwa, the native word for bear, was a noisy mongrel terrier, forever teased with a hefty name. Miinan, the word for blueberry, named for the color of her heavy coat, and Queena, a rangy reservation basset hound and golden retriever mongrel, nicknamed in honor of the famous coloratura soprano at the Metropolitan Opera, were the two musical mongrels at Manidoo Mansion.

Dummy saluted opera sopranos with two handsome hand puppets, and marvelous truth stories were told about the great performances of mongrel singers. The Debwe truth stories were innate native scenes and related to creature voices and the elusive tease of creation and memory, and the stories continued in the adventures of earth divers and native tricksters. The original truth stories were about the mystery of luminescence, that shimmer and natural motion of blue light, and about natives who once danced with animals and chanted to the clouds. Later the visionary stories were told about totemic unions, erotic winks, and the common tricks of creation. Debwe stories revealed natural motion, the flight of a native dream song, the touch and fade of winter, and the steady flow of the great river, and landed in a hand puppet show of operatic mongrels.

The two rough and ready hand puppets, presents to my brother and me, became our curious new voices as veterans of the First World War. The two puppets, in the care of my brother, first told stories of our coax and cover as veterans in the Bonus Expeditionary Force that summer at Capitol Hill in Washington.

By Now Beaulieu rode Treaty, a native farm horse, from Bad Boy Lake to the Exhibition of Blue Ravens at the Ogema Train Station. Treaty, once the wagon horse at the Leecy Hotel, slowly clopped along the platform. She pitched her head near the abstract watercolor scenes. The mongrels moaned in the presence of a horse but were not shied. By Now had served as an army nurse and was ready to march with us and other bonus veterans at Capitol Hill. Walter Waters, the inspired leader of the overnight Bonus Army, and thousands of veterans from around the country were on their way to demand a bonus payment from the United States Congress.

The Ice Woman, or Mikwan Ekwe, was an elusive winter menace, a native enchanter of quietus. She lurked around the woodsy lakes on cold and clear nights, a wispy shadow, and with erotic whispers lured lonesome native hunters to rest in the pure snow, a serene death with the sound of lusty moans, but since the fur trade, the waves of deadly diseases, shamanic deceit, wars, extreme economic depressions, poverty, and hunger, and with the scarcity of totems and game the old icy stories were reimagined without winter and told

in every season of the year. The urgent croak of ravens in the paper birch and that native dream song of “summer in the spring” became our new stories to outlive the treacherous tease of winter and poverty.

Miss Heady, our language teacher at the government school, taught us the word “quietus,” and she used that word in precise conversations. Quietus was the absence of nature, never the scenes of bear walks or kill-deer deception, but she never became a government teacher to wrangle with wild creatures, furred or feathered, or to treasure the noise of the seasons. Naturally, she had never been enticed by the stories of the Ice Woman. Aloysius, my brother, actually painted a great blue raven named Quietus, the blue shadows of bloody broken wings over the heaves and mounds of snow.

Heady confirmed in every sentence that she was a creature of bloodline clarity, the quietus of eastern culture and manners, and concealed two eastern cats, fussy shorthairs, at her federal apartment. Domestic cats had never earned the character of mongrels, and not many natives nurtured indoor cats on the reservation, only lonesome widows who had returned from cities to federal musters, covenants of service, and treachery in the ruins of the white pine and liberty.

Dummy teased my brother and me with silent beams, tics, and puckers, and the gestures of the two puppets were wild, bouncy, and generous. The Ice Woman cocked her head, raised a spiky wooden finger, trembled, and then moved closer and caressed my shoulder. My entire body shivered with the pose of that icy touch.

The Niinag Trickster bumped my brother on the chest and cheek with his giant wooden penis. The touch of the icy puppet was an ominous scene, and the punch of a wooden penis was quirky and comical, but not an easy story to relate with friends. These were the presents of the short, stout, and shrewd mute maestro of native puppetry.

Dummy handed over the two weathered puppets with a noticeable hesitation, and the uncertainty may have been second thoughts or a secret sense of native custody. Rightly, that gift of puppets was a waver in a world of chance, but never a slight. Pussy Beaulieu, her great aunt, had carved the two puppet heads from fallen paper birch, and the crude clothes were fashioned with remnants of mission vestments and school uniforms. The Ice Woman wore a silvery smock with crocheted hearts on the sleeves, and the huge wooden brow of the puppet was painted white, nicked and stained with age. The Niinag Trickster wore leather chaps, a bisected breechclout, and a green fedora with a curved brim. Black fedoras were the fashion of native men at the time. The trickster carried a medicine pouch and a wide black sash decorated with blue beaded flowers. Trickster characters were imagined scenes of sexual conversions in some truth stories, bold, cocky, chancy, and capricious, and at the same time the brazen puppet feigned vulnerability in hand gestures and jerky motions.

Dummy guided my hand under the silvery smock of the risky Ice Woman, and with the steady frown of a shaman she slowly aimed my fingers into the hollow head, sleeves, and blunt hands. The fingers were gnarled willow twigs. The puppet came alive in my hand and waved at the priest and station agent on the platform, and then pointed at each abstract painting in the Blue Ravens Exhibition mounted at the Ogema Train Station.

The Ice Woman was once an incredible creature of the winter nights, and at the train station that afternoon the puppet inspired memories of winter in the spring with the slightest hand motions, a hasty bow, jerky turns, a wave of the head, and teases with an erotic shimmy. No one escaped the mighty gestures and enticement of the Ice Woman.

Dummy backed away from my hand gestures.

The Ice Woman raised a wintery hand, waved a stick finger, and asked the mission priest if he had ever dreamed about a rest in the snow, an eternal slumber in the paradise of winter. My first voice as an icy puppet should have been more enticing, elusive, at least a lusty tease, but instead the words were taut, an uneasy parody of vaudeville. The priest excused the caricature and leaned closer to the puppet in my hand. “Yes, once or twice near the mission, enchanted by the whispers in winter trees, and the heavy waves of snow over the graves,” he confessed, in that new game of puppets at the station. The Ice Woman pretended to be demure in my hand as the priest reached out to favor the wind checked birch head of the creature.

The Ice Woman turned away.

The Jesuit priest was an unusual missioner with a sense of chance, of humor, and he seemed to appreciate the native decoys of nature and nurture in spite of my clumsy puppet parody. He was short, wore a biretta and cassock, a more distinctive costume than the stern and steady Benedictine priests who ruled Saint Benedict’s Mission on the White Earth Reservation. The Benedictines banished the puppets and strained to favor the abstract images of blue ravens, and a priest once urged my brother to more accurately represent the carrion crow as black, black, black, not blue. Most of the priests were truly wounded by credence, burdened by the culture of sacrifice and churchy colors, scared by the bold swagger and steady throaty croak of ravens at the mission cemetery. The priests were forever separated from creative scenes, the eternal natural motion of the seasons, and blue ravens in the sudden glance of morning sunlight.

Salo, the stout station agent, was a raven crony who shared his lunch with ravens and practiced the mighty croaks, but he was anxious around priests, and he was doubly shied by the strange gestures of puppets. He worried that puppets were shadows and souls of the dead, and ruled the world with jerky motions and satire. He knew my brother and me as war veterans, of course, and some twenty years earlier as the native boys who hawked the Tomahawk newspaper at the very same Ogema Train Station.

Salo turned away that afternoon to avoid the priest and our puppets, and pretended to examine the art more closely. He studied the shadows over the stadiums of war, fractured faces of soldiers and animals in bold colors, the double faces of the fur trade crusade with bright broken brows, cracks, creases, and distorted gestures of native soldiers as abstract blue ravens at the platform exhibition.

Aloysius, who could not escape the nickname Blue Raven, changed the style and form of his earlier ravens, the once great abstract blue wings with traces of rouge were revived with bold colors and broken portrayals, the natural motion of expressionism, the visionary sublime, or original totemic fauvism. My brother read newspaper stories and art magazines about modern art, abstract expressionism, the cubist teases, and together we visited museums and galleries in Paris at the end of the First World War.

Blue Raven was inspired by the dreamy traces and scenes of Henri Rousseau, the marvelous portraits, feisty faces, cerise lips, and the bold gawky features painted by Chaïm Soutine, the enchantment of colors and shapes by Henri Matisse, and, of course, the memorable, visionary, and naïve primitivism of Paul Gauguin.

Blue Raven was a spirited painter, and forever haunted by the crevice of nightmares, the broken scenes of memories, and dead totemic animals of the dreadful fur trade. He was tormented with the war scenes of humans and animals and created abstract blue ravens and fractured scenes of bold colors, an original style of totemic fauvism. The scenes were contorted motion, the maelstrom of natural motion with traces of animals, birds, and humans in the guise of ravens.

Marc Chagall painted double faces in motion.

Henri Rousseau created great forests of motion.

Blue Raven created the clout of natural motion and the truth stories of totemic fauvism. The French fur trade was an eternal cultural shame, and yet the memory of totemic animals continued as a source of stories and images in native art and literature.

The totemic images in my stories were more sublime than fauvism, and the animals were envisioned with the sway of poetic scenes, an ironic tease, the surreal words of description, and traces of visionary motion, that cosmic motion revealed in the expressionism of ancient rock and the cave art of our ancestors.

Salo praised the creative visions of my brother, “the fury of blue ravens, the bright colors and scraps of soldiers,” great abstract wings and “unearthly crimson claws,” and the station agent generously repeated scenes, to be fair in his favor, from my storie

s about the ruins of war and the later encounters with surreal and subversive art and literature in Paris.

Aloysius was directed to insert his fingers in the head, hands, and giant penis of the Niinag Trickster. He actually thrust his hand into the floppy puppet with a great gesture of confidence. He raised the wooden penis and shouted out comments about the sexual nature of totemic art and the lusty turn of seasons, nippy at the start and then a warm breeze with balmy seductions. Churchy art, the puppet shouted, was bloody, erotic, perverse, and the sacrifice of virgins. The most erotic and ironic native stories were about the giant penis of the trickster. The mission priests, nuns, missionaries, and native converts shunned the trickster and never ventured to repeat the lusty niinag stories.

The priapic trickster was overturned by the aroused heft of his huge penis in many versions of the lusty stories, and in other stories the trickster pecker was envied as a weather vane, ensnared with a shaman in a hollow tree trunk, captured by a hungry bear, the steady stump for a king-fisher or a paddle in a birch bark canoe, and a niinag disguised as a handsome lover in the natural, native course of jealousy.

Tricksters were always in motion, the natural motion of seasons and most stories, and the risky scenes were about incredible vitality, wily earth diver creations, magical and awkward conversions and sexual routs, mercy mockery, and hoaxers of jealousy. The ruckus created in trickster stories was never resolved with clerical or moral lessons, except in those chaste and heartless translations by early discoverers and righteous missionaries. The most erotic trickster penis stories were denatured by the romantic guardians of native cultures, and by the federal agents of decorous and devious assimilation policies.

Dummy was once captivated by words, entranced as a child by chant and chorus, and truly aroused by the voices of coloratura sopranos. She was inspired by the operatic sound of some words, the tones and sentiments, such as the last rose of summer, precious heart, the tender hand that rocks the cradle, old men and rivers, and the moody native dream songs, summer in the spring, beautiful as the roses, and the sky loves to hear my voice. Since the savagery of the firestorm that turned her love to white ash she mouthed the poetry and operatic arias only in silence, and was moved to tears by the voices of sopranos, but she never voiced a sound herself, not a single note or word, no rumors, rage, whimpers, whispers, or promises. Instead, she trained two tuneful mongrels to read the sly gestures of the opera puppets and to then sing, or rather bay and moan in various tones and unusual harmonies.

Native Tributes

Native Tributes Blue Ravens: Historical Novel

Blue Ravens: Historical Novel